How Life Began on Earth — And Why It Happened Fast

How Life Began on Earth — And Why It Happened Fast

We still don’t know exactly how life began, but one thing is clear: once Earth was ready, life didn’t waste time showing up.

Scientists are working with just one example — our own planet — so it’s hard to say how common life really is. Still, recent discoveries give strong hints that life can emerge quickly under the right conditions.

At some point in Earth’s early history, a mix of chemicals came together, powered by heat or minerals, and formed the first living cell. This moment — the birth of life — set everything in motion. But figuring out when this happened isn’t easy. Billions of years have blurred the evidence.

Still, clues are adding up. Signs of life have been found in rocks dating back as far as 4.2 billion years — not long after Earth itself formed. Ancient bacterial mats called stromatolites appear in the fossil record from 3.7 billion years ago. Tiny structures in Canadian rocks may be even older — possibly 4.28 billion years old.

LUCA: The Root of All Life

To trace life’s earliest days, scientists look at DNA. By comparing genes across species, they’ve inferred the existence of LUCA — the Last Universal Common Ancestor. This single-celled organism is the ancestor of all life today, from microbes to humans. Evidence suggests LUCA lived at least 3.6 billion years ago, maybe even earlier.

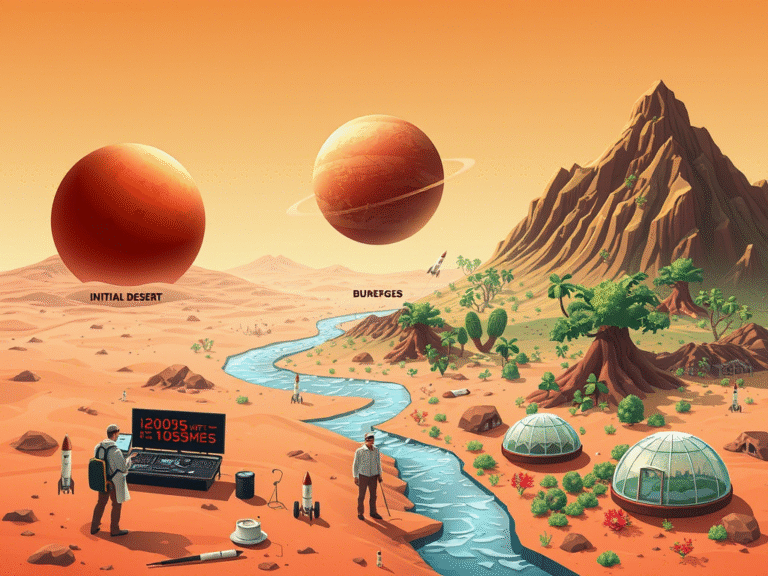

What does all this mean? Life got started surprisingly fast after Earth became stable. If the same rules apply elsewhere, then planets like ours might not stay lifeless for long.

The fact that life appeared early in Earth’s history might suggest that forming life is easy under the right conditions. But there’s a catch: we only have one example — our planet — so it’s hard to be sure.

David Kipping, an astronomer, looked into this using statistical tools like Bayesian analysis . He found that based on the earliest known signs of life (dating back about 3.7 billion years), the odds favor the idea that life can form quickly — with initial estimates at around 3:1 in favor of rapid abiogenesis.

Newer evidence — including findings related to LUCA , the Last Universal Common Ancestor of all life, dated as far back as 4.2 billion years ago — strengthened those odds to over 13:1 , offering what Kipping calls formally strong support for the theory that life gets started fast when conditions are right.

But here’s the twist: just because life began quickly doesn’t mean intelligent life does too.

It took nearly 4 billion years after life first appeared for humans to evolve. And since Earth’s habitable window is limited (likely ending in less than a billion years due to the Sun’s aging), intelligent life had to start early — and maybe did so under unusual circumstances.

This brings us to the Weak Anthropic Principle : we’re here to ask these questions only because things worked out the way they did. If life had taken longer to appear, we might not exist to observe it.

Kipping also considers other ideas, like the Silurian Hypothesis , which asks whether science could detect signs of ancient industrial civilizations — even ones that existed hundreds of millions of years ago. While speculative, it shows how scientists are pushing the boundaries of what we consider possible.

Still, Kipping stresses that his findings don’t prove life — especially intelligent life — is common. Earth may still be rare, or even unique. For now, we’re working with just one data point.

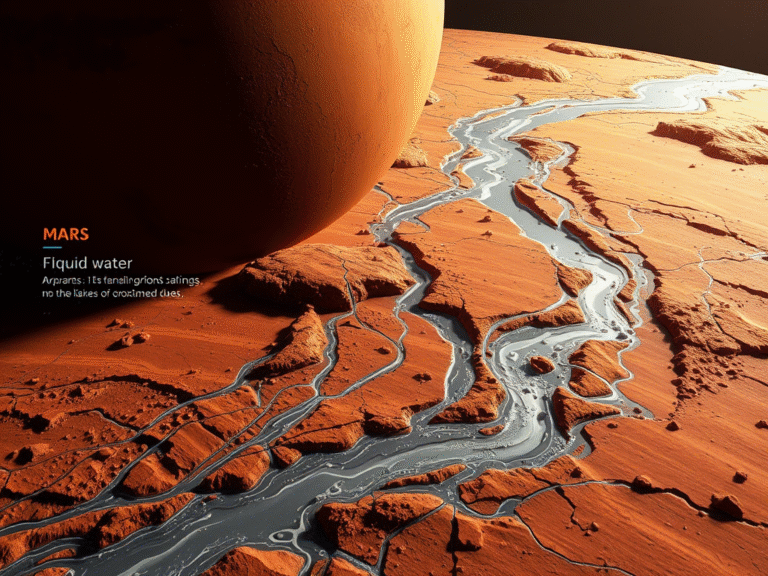

Finding signs of life beyond Earth — whether on Mars, Europa, Enceladus, or distant exoplanets — would change everything. Until then, we keep asking: How common are planets like ours? And how likely is life to begin?